From hot war to trade war

I confess I did not expect Iran to put up such a weak response to the US bombing run. Their options were limited by the decline in their own arsenal after weeks of missile launches against Israel, losses imposed on Hamas, Hezbollah and the Houthis, and the collapse of the Syrian regime. But warning the Americans to clear out before sending a few rockets into an empty base in Qatar was clearly intended to de-escalate the situation despite the serious damage the US raid inflicted. The US attack does appear to have convinced Iran to try to find a diplomatic way out of the “12 Day War” with Israel. We can only hope it lasts.

With the Israel-Iran conflict now over — in Trump’s view — the President’s attention can now turn again to trade. To the surprise of absolutely no-one, including probably Prime Minister Carney, President Trump announced on Friday that he was cutting off trade negotiations with Canada (were any underway?) in response to the Canadian government’s decision to proceed with enforcing its Digital Services Tax on June 30. Trump’s made it clear that these taxes on large digital service providers — mostly American — were unacceptable and would be grounds for setting a relatively high ‘reciprocal’ tariff. Ever since Canada and some European countries began preparing their DSTs, they have been opposed by US governments.

True, Trump seems to have abandoned other grounds for setting high tariffs — he hasn’t objected to the UK or Indonesian VATs, for example, when reaching accommodations with them over trade. But with just over a week to go before the April 9 90-day negotiation window closes, this decision is a reminder that Trump’s ‘reciprocal’ tariffs are a response to many more supposed grievances than just the level of tariffs other countries impose on imports from the US.

Just over a week? Or is it two months? Treasury Secretary Bessent continues to hold out hope that countries that are negotiating ‘in good faith’ will be spared a tariff increase on July 9 and expects that those countries will be able to finalize deals with the US by Labor Day. Canada is clearly in the doghouse. Maybe they alone will get a letter next week. Or maybe not. Trump himself on Friday said the deadline wasn’t binding. “We can do whatever we want. We could extend it. We could make it shorter.”

And speaking of “deals”, the US and China finalized last week the agreement reached in London on June 10 to restore the May 15 Geneva agreement. (The Chinese announcement is here). This paves the way for higher exports of rare earth materials to the US in exchange for the US removing the additional export controls — on electronic design automation software, aircraft parts and chemicals — introduced in late May. The US will apparently also resume issuing visas to Chinese student. That May 15 agreement was supposed to create a 90-day truce, bringing US tariffs down to about 55% (not including sectoral tariffs) and Chinese tariffs down to about 30%.

Whether the Geneva agreement’s 90-day window is still in force (has it been re-set to start last week?) is perhaps linked to whether the July 9 deadline still means anything. We’ll find out over the next ten days. The purpose of these 90-day negotiation windows was presumably intended to lend some urgency to the process. But the Trump administration itself doesn’t seem to be in a hurry to conclude negotiations. Commerce Secretary Lutnick has, since April, been repeating that a host of agreements are imminent; just as Trump has for many weeks been saying that countries can expect to receive a letter in the next couple of weeks from him or Secretary Bessent with their new tariff number. These self-imposed deadlines have been broken so consistently that they no longer carry any credibility. For Trump, “two weeks” seems to be shorthand for ‘I can’t be bothered to think about this right now.’

Trump’s ill-advised attack on Powell

Trump has also renewed his personal attacks on Fed Chair Powell suggesting on Friday that he might name Powell’s successor soon, nearly a year before Powell’s term ends. The four names most commonly listed as likely successors to Powell are current Fed Governor Chris Waller, former Governor Kevin Warsh, Secretary Bessent and National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett.

Naming a ‘shadow Chair’ would be, in my view, a bad idea. But not for the reason most people seem to worry about. A ‘shadow chair’ wouldn’t increase uncertainty about current Fed policy. Waller is already a voting member of the FOMC and hasn’t been able to persuade the rest of the committee to support an early rate cut. Pre-nominating another person to the job just adds another voice outside the Fed calling for rate cuts.

But pre-announcing the nomination of Powell’s successor may stiffen the resolve of voting members who aren’t yet decided on the need for a rate cut but might vote against one if only to try to protect the integrity of the process. So Trump may be less likely to get the rate cuts he thinks the US needs.

Moreover, a ‘shadow Chair’ would be expected to go public with their views on interest rates over the next eleven months. Assuming they immediately come out in favour of substantial rate cuts, their credibility as Chair could be significantly damaged if in the interim inflation (or economic growth) surprises to the upside. They could find themselves being formally nominated early next year with a track record of incompetence already established.

The US data are still distorted by previous tariff threats. Just as front-loading of imports to get ahead of tariffs brought demand forward (but greatly increased the trade deficit) in Q1, as that pre-emptive behavior subsided, retail sales have softened, reverting to trend. But core PCE inflation has remained at essentially 2.7% (that was in fact the May rate of core inflation) for a year now. And an unemployment rate of 4.2% is at the low end of the range of estimates of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). I think Powell is correct to say that until we know how high tariffs are going to be set and how much even the current tariffs are passed on to consumers, it’s too soon for the Fed to be cutting rates with an inflation rate stuck well above target.

Markets rallied on easing of Middle East tensions

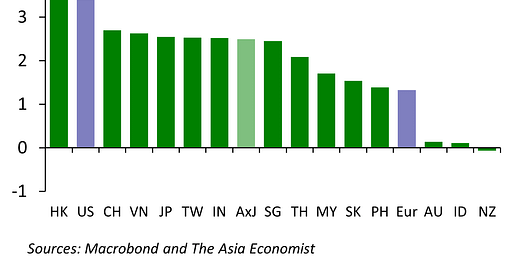

Markets responded very positively — with reason — to the aftermath of the US attack on Iran. Crude oil prices fell 9% on Monday and were down about 12% by the end of the week. US stocks rallied to a new all-time high, rising 3.4% for the week — better than Europe and all the APAC markets but Hong Kong.

But even if they weren’t quite as buoyant as in the US, APAC markets generally had a strong week. Only in New Zealand did the market close slightly lower at the end of the week, while gains in Australia and Indonesia were very modest. In most APAC markets, equities rose more than 2% last week on falling oil prices and perceived declining tariff risk.

A new all-time high for US stocks put the total return on US equities so far this year at 4.5%ytd. This is well below the USD total return on stocks in Europe (24%), Asia ex-Japan (15%) (led by South Korea’s 40% return) and Japan (12%).

US investors have fared better than most advanced economy investors in the bond market, though. So far this year, the 10yr Treasury yield has fallen 29bps, essentially returning to where yields were on election night. Yields in Japan and Germany, conversely, have risen more than 20bps this year. Other Euro Area yields have risen less than this, but have generally risen significantly relative to USD yields. Last week again saw a decline in US yields (-8bps) — encouraged by Trump’s renewed attack on Powell — but higher yields in Germany (+8bps) and Japan (+2bps). Most APAC markets saw lower yields last week, but only in the Philippines, New Zealand and Hong Kong did yields fall more than in the US.

This tendency for euro area and Japanese yields to rise while US yields fell explains why the yen and Euro have appreciated so strongly against the dollar this year. The weakness in the dollar — in trade-weighted terms it is on track for the worst first-half since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 — is not a surprise when you consider how yields have behaved. The surprise is that Trump’s tariffs were expected to be — indeed, need to be if they are to have the desired result — inflationary in the US and deflationary abroad. So the surprise is not really that the dollar is weak, the surprise is that in the face of rising tariffs and a rising fiscal deficit US yields have fallen.

This decline in US bond yields more than any other indicator reflects, I think, an expectation on the part of investors that Trump will back down on tariffs. US tariffs have already risen faster than in any year since 1821 and are now at the highest level since 1938. Note, though, that the tariff revenue collected by the US government in May, implied an actual effective tariff rate of just over 8% — well below the estimated de jure rate of more than 14%. The tariffs haven’t fully taken effect yet. This helps to explain why fixed income markets do not show any concern about higher inflation while US firms and households do expect higher inflation.

There is already reason to expect, I think, that markets will be proved wrong in their benign view of the impact of the tariffs already imposed. And if next week tariffs are raised again there will be even more reason, I would say, for markets to sell off.

But the dollar has behaved in a puzzling way for part of the year. Normally, higher yields in the US relative to other economies are associated with a stronger dollar and lower relative yields with weaker dollar. But as this chart relating relative yields to the EUR/USD exchange rate shows, for most of April and May the opposite happened. When Trump announced the ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on April 2 US yields plunged but then when he suspended them on April 9 yields rose even higher than they had previously been. The market treated these tariffs as a recessionary shock rather than an inflationary shock. But as US yields rebounded after April 9, the euro appreciated. And for most of the next month there was a curiously inverse relationship between relative yields in the US and the euro.

This pattern is, as I and other commentators observed at the time, what we normally see in emerging markets. The interpretation is that higher US yields were being driven to some extent by capital outflows from the bond market. So higher US yields, instead of attracting capital inflows (and strengthening the dollar) were a result of capital outflows (and so a weaker dollar). In June, the ‘normal’ pattern has returned. Falling relative yields in the US have been associated with a weaker dollar.

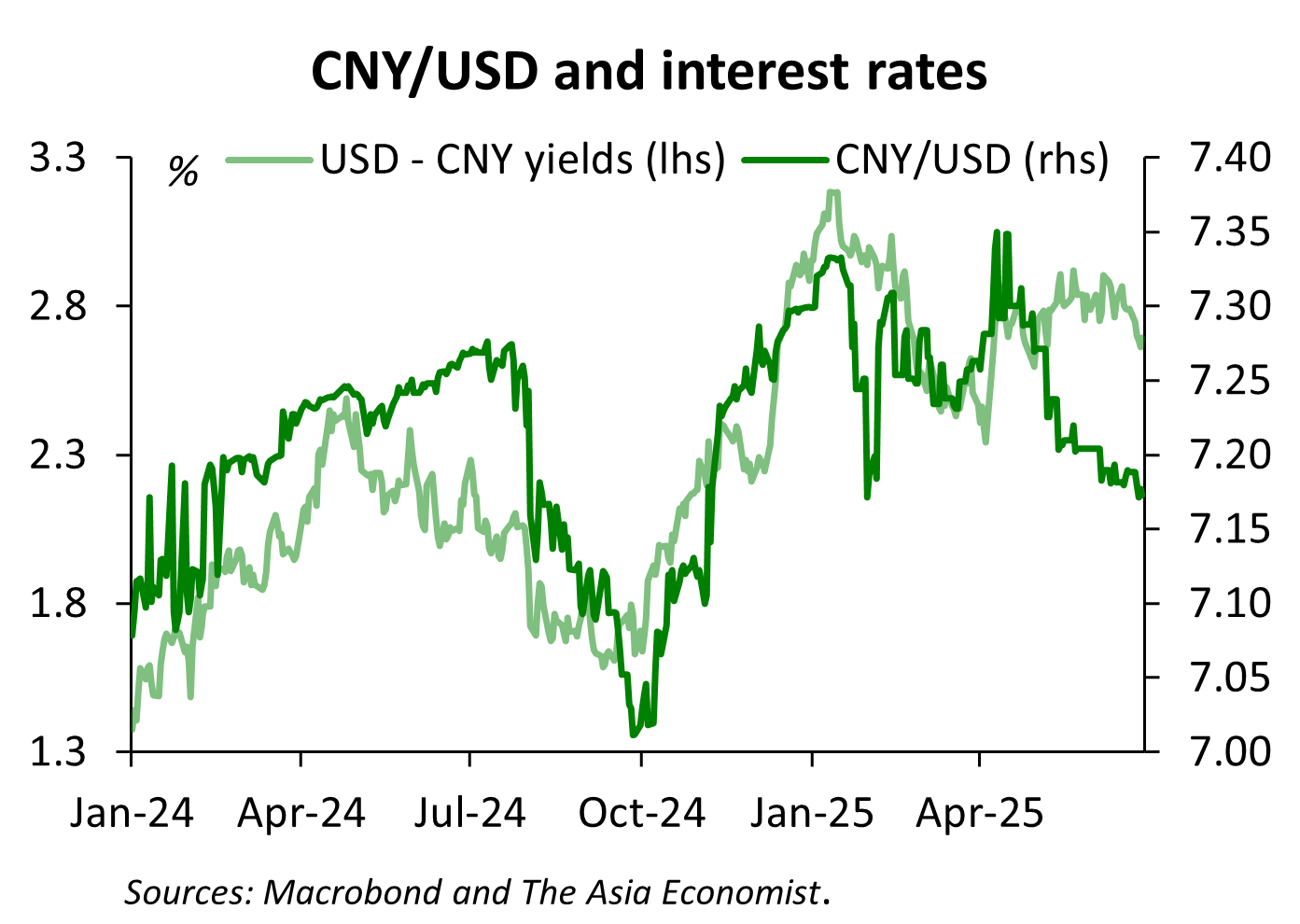

We saw something similar, but less pronounced, in the CNY exchange rate. Many commentators under-appreciate, in my view, the significance of relative interest rates as a driver of the CNY/USD exchange rate since the pandemic — indicative of a weakening of equity-related capital flows more than of a relaxation of capital controls. Prior to April, higher relative yields in the US — say, throughout Q4 last year — had been associated with a weaker yuan. But in China too, during most of April and May, the CNY appreciated while US yields edged higher relative to Chinese yields. But here too, since the beginning of June, the ‘normal’ pattern has returned. The CNY has appreciated in an environment of falling relative yields in the US.

I’ll go on now to discuss last week’s policy announcement from the Bank of Thailand, fiscal policy in the Philippines and important data issued in China, Japan, Australia and Malaysia.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Asia Economist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.