Mission accomplished?

President Trump’s decision to bomb Iran is an uncharacteristically conventional Republican approach to Middle East policy. He withdrew the US from the JCPOA, which had halted Iran’s uranium enrichment program, in 2018 and then used the subsequent resumption of that enrichment effort to justify an attack yesterday despite the judgement of his own national intelligence staff that Iran was not working on a nuclear weapon. While he may have (that’s not yet certain) destroyed Iran’s capability to take that step now, he’s likely convinced them that they most urgently need to as soon as possible.

Those bombs have not, moreover, destroyed the capacity of the Iranian state to wage war although its apparent lack of any air defenses makes it extremely dangerous to retaliate directly. Iran’s options are limited, though. Russia is in no position to provide material support and I think China would be averse to doing anything overt as well. China’s interest in Iran is mainly economic — it needs their oil. It has avoided being dragged into Russia’s war on Ukraine and will likely avoid the same with Iran. Iran’s regional clients and proxies have been greatly weakened by Israeli and American attacks over the past 18 months but retain some capability to strike at US assets. The Houthis could be useful if Iran decides to close the Strait of Hormuz, something the punters on Polymarket think is likely at some point.

The main risk to Trump is that Iranian retaliation draws the US into moving more troops into the region. Even his most ardent supporters might rebel at a betrayal of his promise not to enter into another ‘forever war’. Trump thinks instead that yesterday’s strikes will compel the Iranian government to sue for peace. It’s unclear Israel would agree to any terms while it has the upper hand. And while the US says it isn’t trying to effect regime change in Tehran, Israel most certainly is. The Iranian regime may not see their options the way the US thinks they should.

Bitcoin pricing since the attack was announced does not suggest investors are overly concerned. BTC, which rose on the news of the attack, is down about 3.8% since Friday evening. Interestingly, most of that decline (3.2%) has happened since the Defense Department press conference began this morning. So stocks will likely open slightly down on Monday. But for Asia Pacific economies, the risk that oil flows through the Gulf may be obstructed is more important and I’d expect stocks to be even weaker than in the US on Monday.

As for oil, as of Friday afternoon, the Middle Eastern benchmark price had risen 23% since the end of May. Any threat to oil exports from the region will push prices materially higher.

Estimating the inflationary consequence of an oil price shock

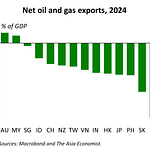

Last week, I showed which economies in the region are most dependent on oil imports: Thailand and South Korea. Most APAC economies have an oil and gas import bill of about 2.5% of GDP, but for Thailand and South Korea it’s more than double that. Australia and Malaysia are modest net exporters of oil and gas.

What about the inflation consequences? As I said last week, an oil price spike will at least temporarily weaken the disinflationary trend in the region. How much the consumer price index rises will depend firstly on how sensitive retail prices for petrol and household gas are and secondly on their weights in the CPI. Household fuels are more commonly subsidized and are generally a small component of the CPI. It’s a little more complicated if electricity is generated by gas-burning power plants and prices aren’t subsidized.

But here I’ll focus on the more common influence on the CPI of an oil price shock: automotive fuel prices. In China, to illustrate, fuel prices are not subsidized at the margin — there’s a pricing mechanism that passes on higher crude oil prices to consumers. So the CPI component “automotive fuel and parts” rises and falls very closely with fluctuations in the CNY value of a barrel of crude oil.

A 10% rise in the CNY crude oil price has, since 2016, caused a 3.5% rise in the fuel and parts component of the CPI. I estimate (the NBS doesn’t publish it) that this component has, coincidentally, a 3.5% weight in the CPI. So, a 20% rise in the Middle Eastern crude oil price could be expected to add about 0.25% to the headline CPI (2*3.5*3.5%). Household utilities costs rise and fall very slightly in response to oil price shocks. We don’t get much detail in the CPI report, but “water, electricity and fuels” has about a 5.1% weight in the CPI but a 10% rise in crude oil prices leads to only about a 0.3% rise in this CPI component. So we can safely ignore it.

The following chart shows the sensitivity of the automotive fuel component of the CPI index in each economy to a 10% rise in the local currency value of a barrel of crude oil since 2016.

The sensitivity will be higher the lower the refining margin and the the lower the subsidy on retail fuel prices and the lower the tax rate on fuel. I’ve excluded Indonesia and Malaysia from this chart because they do subsidize most automotive fuel prices. On average, across these economies, a 10% rise in crude oil prices leads to about a 2.9% rise in retail gasoline prices.

Then there’s the matter of the weight of fuel prices in the consumption basket. This is surprisingly high in Thailand and, thanks to very efficient mass transit, very low in Hong Kong and Singapore. For most other economies, automotive fuel (petrol and diesel) accounts for about 2.8% of the CPI.

Multiplying the sensitivity by the weight gives us a rough estimate of the ‘first round’ effect of a rise in crude oil prices on inflation. In Hong Kong and Singapore, low sensitivities and very low weights imply very little immediate exposure to an oil price shock. India and Japan are only slightly more exposed — a 20% rise in crude oil prices would lead to about a 0.1% rise in the CPI. At the other extreme, Thailand, with a very high weight and higher-than-average sensitivity can expect the CPI to rise 0.5% the month after a 20% crude oil price shock. For the other economies the effect would be about half that.

That’s the ‘first round’ effect. The ‘second round’ effects come from higher transportation costs being passed on to prices of other goods. This can be especially important for food prices where there’s often both a high energy component to the cost of production and high distribution costs. While central banks will try to avoid reacting to the first round effects, if they see higher oil prices being passed through to non-fuel prices more generally, it becomes harder to cut rates.

No progress on tariffs for APAC

Donald Trump left the G7 summit early on Monday — he didn’t even stay for dinner. Asia Pacific leaders who were invited to the summit and had hoped for a chance to negotiate trade deals one-on-one with the President will have been disappointed. Trump and Starmer signed something — a press release apparently — and there’s talk of progress towards a deal with the EU that doesn’t touch on tariffs. And apparently Trump thinks the US and Canada can reach some kind of agreement over the next 30 days. But there’s been no word of progress towards a deal with any APAC economy over the past week. Indeed, relations with Japan seem to have deteriorated over US pressure on Japan to further increase their defense budget.

With two weeks to go, it looks increasingly like it’ll simply be up to President Trump to decide some time in the next week or so how high a tariff wall he wants to erect around the US economy. My bias is still that ‘the higher the better’ is how he looks at it, and with scant evidence as yet that tariffs are being passed on to consumers (importers, though, are paying the tariffs), it’ll be hard for anyone in the administration to argue against a high number if that’s what he chooses.

So, while the market seems to have decided that the current 10% base rate (plus sector-specific tariffs, including 50% on steel and aluminium and 25% on most automobiles and parts) will prevail indefinitely, I think the risk of tariffs higher than this very real. And there are still sectoral tariffs on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors (and anything that includes semiconductors) to come.

After a little front-loading of exports to the US early in the year, as I reported last week China’s exports to the US plunged 34.5%yoy in May after falling 21% in April and rising 5% in Q1. Exports to the rest of the world, though, rose 11.5% in May, only slight slower than April’s 13%. A key question for China — indeed, the APAC region — is whether exports to the rest of the world can continue to grow if exports to the US don’t.

Ordinarily, China’s exports to the rest of the world track exports to the US closely. There are two very good reasons for this. Firstly, exports of intermediate goods feeding into regional supply chains that ultimately have the US as an important final customer (i.e., most supply chains) will contract rapidly if US demand weakens. Second, even sales of final goods will be negatively affected by weaker US demand if China’s customers in third countries are themselves exporters to the US and therefore suffer a loss of income from a decline in their exports to the US.

Now, in 2019, falling exports to the US after Trump’s first tariff increase were accompanied by weaker but still growing exports to the rest of the world. This was partly because Chinese firms exported to the US through third countries and the US didn’t crack down on that trade forcefully enough. We’ve seen that this US administration has already warned countries that they will not tolerate tariff evasion through transshipments. Indeed, in the US-UK trade deal even Chinese-owned companies in the UK are not eligible for the tariff relief the deal provides other UK-based firms.

So my expectation is that Chinese exports to the rest of the world will soon weaken quite dramatically unless US-bound trade recovers. But this is a forecast and I’ll be guided by the data.

Bangko Sentral cuts rates others keep rates unchanged

Not surprisingly, as I suggested last week, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas cut its policy rates last week while the Bank of Japan, Bank Indonesia and the Central Bank of China in Taiwan kept rates unchanged. As did the Fed.

During his press conference following the announcement of the FOMC decision, Chair Powell spoke of emerging risks to inflation from tariffs in the following terms: “goods being sold at retailers today may have been imported several months ago, before tariffs were imposed…we do also see price increases in some of the relevant categories like personal computers and audiovisual equipment, things like that, that are attributable to tariff increases.” So while the labour market, and the economy generally, remains in good shape, Powell and most FOMC members are concerned about the inflationary impact of tariffs. While he noted that the impact is highly uncertain, he reiterated that “Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored and to prevent a one-time increase in the price level from becoming an ongoing inflation problem.”

The new economic projections of the FOMC showed a further decline in the Q4 YoY GDP growth forecast to 1.4% from 1.7% in March and 2.1% in December and an increase in the core PCE inflation forecast to 3.1% from 2.8% in March and 2.5% in December. What has not changed, though, is that the median forecast for the Fed funds rate still has two rate cuts before the end of this year.

That’s also what the market is expecting — Fed funds futures are at 3.9% in December — and this might be consistent with a decision to keep the baseline for tariffs at 10% for all countries except China. But even with that I’m less sure there will be room to cut rates twice before year-end. And my bias, as stated above, is that Trump will still push for an increase in tariffs on most imports.

The Bank of Japan’s Policy Board decided, as expected, to keep its policy rates unchanged citing downside risks to the economy, and therefore to inflation, from the US tariff policy. The Board revealed for the first time its plans for the pace of reduction in JGB purchases after Q1 next year. This plan calls for a slower pace of decline from the current JPY400bn per quarter reduction in purchases to a decline of JPY200bn per quarter thereafter.

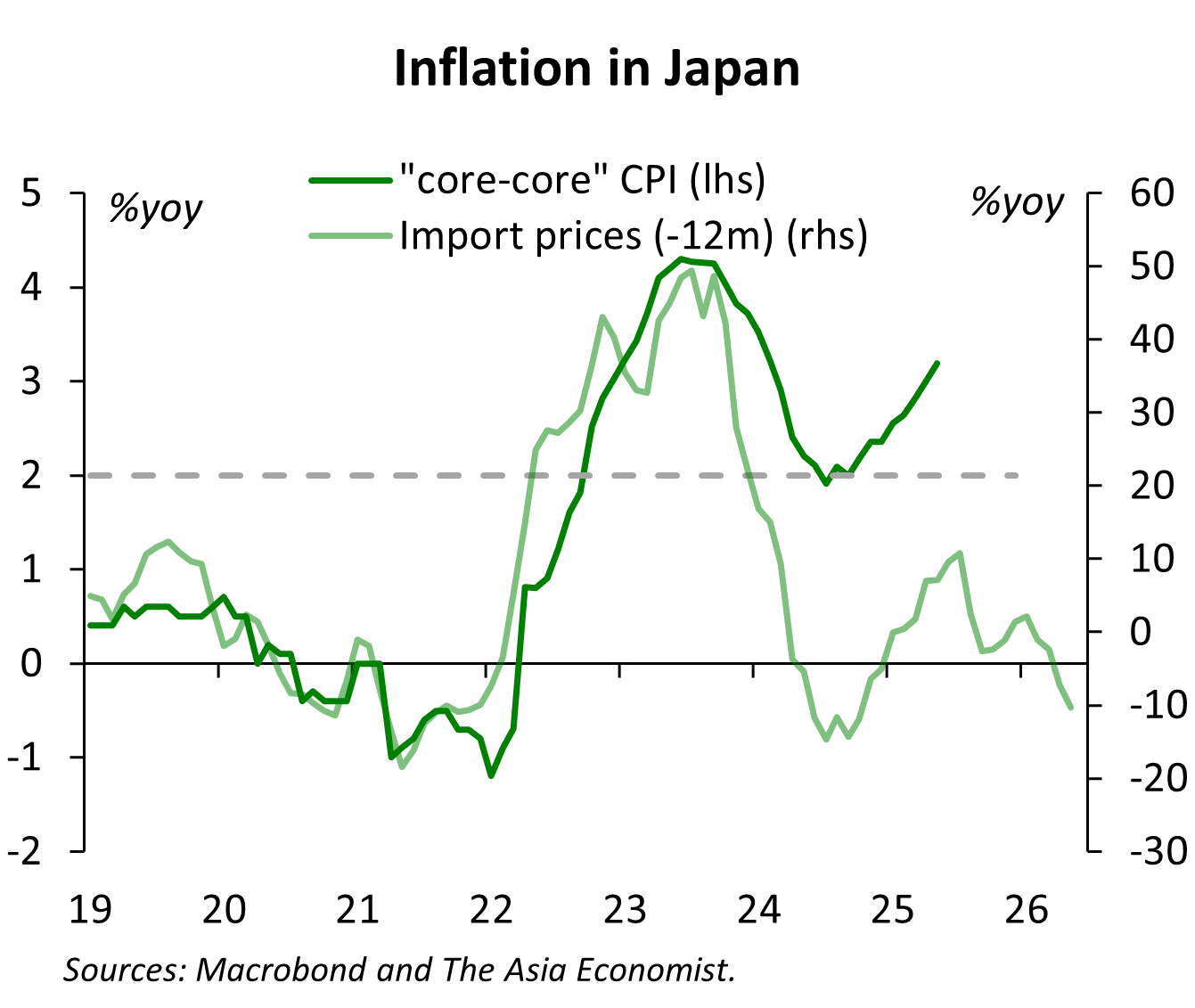

The about-face on inflation since April is quite remarkable, especially as underlying inflation has continued to rise well above the central bank’s target. When I started this newsletter at the beginning of last year, I said that I thought history would judge the BoJ’s tightening policy to be premature, as it was in 2006-07. While the BoJ continues to see underlying inflation as being driven by wage increases, I see it being influenced more by import prices and a weak yen. Note that even though wage growth has been rising over the past year, services price inflation has been slowing. BoJ rate hikes, by strengthening the yen have sowed the seeds for inflation again to undershoot the 2% target rather than leveling off at 2% as the Board expects.

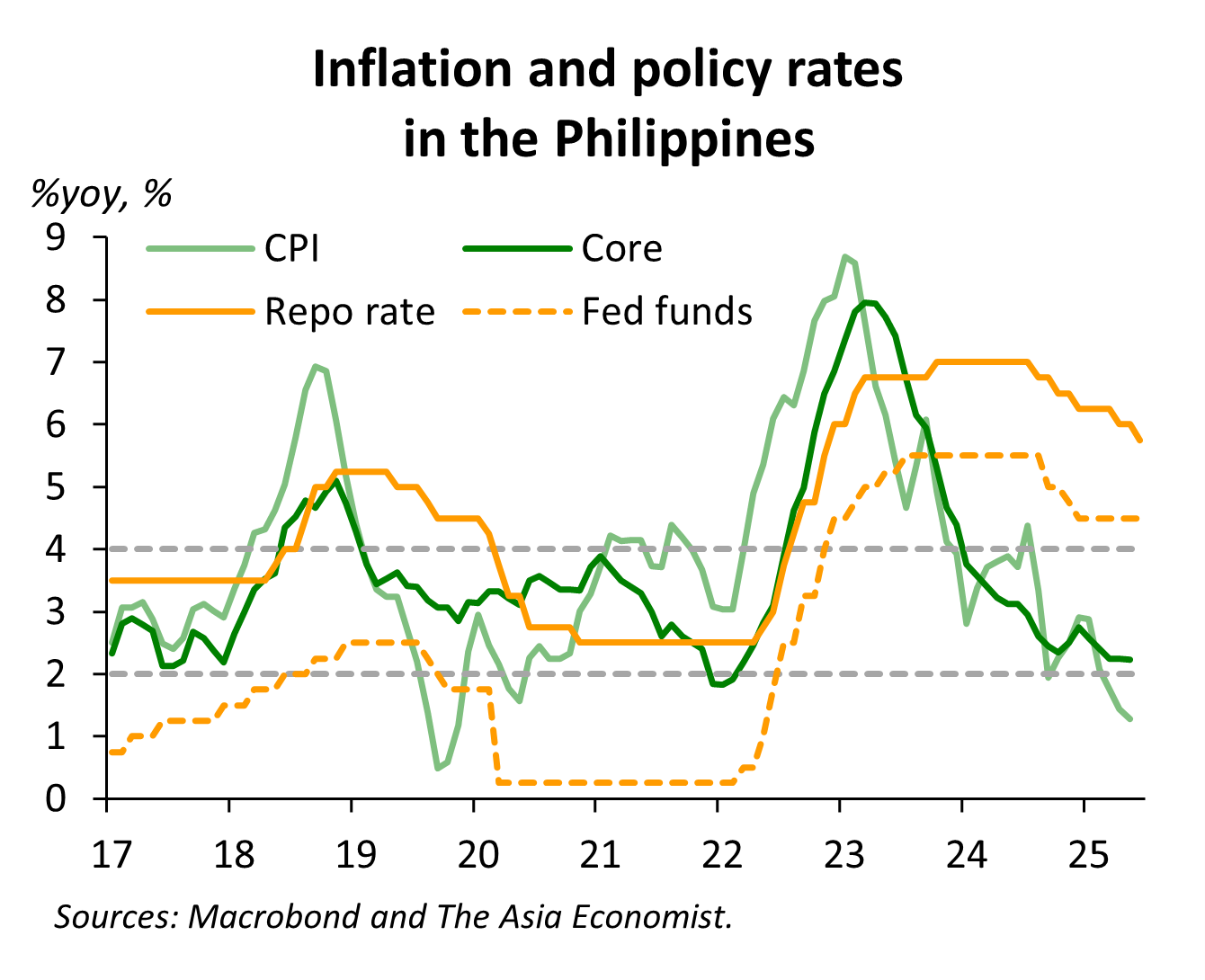

US tariffs are, at the margin, inflationary in the US but deflationary in countries that export to the US. So in the Philippines, the BSP cut its policy rates by 25bps on Thursday after lowering its forecast for inflation this year to 1.6% from 2.4% previously. That brings the overnight repo rate down to 5.75% from the recent high of 7%. The differential between that rate and the Fed funds rate is now 1.25% — it has never been lower. Does that put a floor on the policy rate? The peso was the weakest currency in APAC last week, but most of the depreciation came before the monetary policy announcement.

Bank Indonesia kept its policy rates unchanged, as I expected they would — if only because they had cut rates last month and I thought it would be too early to cut again. They maintained what I consider to be an easing bias: “Moving forward, Bank Indonesia will continue monitoring further room to lower the BI-Rate in pursuit of economic growth, while maintaining inflation within the target range and exchange rate stability in line with economic fundamentals.”

As in the Philippines, the currency is an important consideration in monetary policy decisions in Indonesia. The IDR has been stronger than the peso in recent weeks but weaker year-to-date. The peso was the only reason I thought the BSP might not have cut rates last week. Unlike the Philippines, though, core inflation in Indonesia is rising — albeit only at the middle of the target band. Not yet a barrier to further rate cuts, but something to watch.

There was no surprise when the CBC kept policy rates unchanged. The central bank noted that while US tariffs have led to a weakening of manufacturing activity globally, in fact the opposite has happened in Taiwan. Strong demand for AI chips and semiconductors more broadly have kept Taiwan’s exports growing strongly. Inflation has been slowing very gradually but remains well above what’s normal for Taiwan. The policy statement maintained what I consider to be a neutral outlook on policy.

Market summary

It was a surprisingly quiet week in financial markets again. Even the outbreak of hostilities between Iran and Israel and the possibility that the US might be drawn into it couldn’t dissuade investors from their benign take on the outlook. The market judgement is that the tariff shock is over — there will be no more tariff hikes — and that the inflationary consequences are very minor. Hence, the Fed is on track to cut rates and if the conflict in the Middle East pushes up headline inflation it also will be a temporary phenomenon. We’ll see.

So it was that US stocks were essentially unchanged on the week. So too were Asia ex-Japan markets overall, with South Korea again leading the way higher and Thailand falling further behind. Indonesian stocks were also down significantly last week reflecting concerns about domestic policy — including the revocation of four nickel mining permits last week. Otherwise, while most markets saw declines last week, they were small.

The rebound in South Korean stocks over the past two months has been quite remarkable. Hopes that the political turmoil that erupted with the state of emergency declaration in December is now truly over has seen that market rally more than 30%. South Korea last week pulled slightly ahead of China and the European markets in outperformance since the US election in November.

Bond markets were very mixed last week but in most cases changes in yields were modest. Yields in Canada, the US and Europe fell while most APAC markets saw slightly higher yields. Japan was the most notable exception, but even there the 10yr yield was down only 4bps on Friday.

The US market for the first time in a while behaved like a safe haven during a time of heightened geopolitical risk. While US yields fell, the dollar appreciated against most currencies. The euro weakened by 0.2% and the CAD (with the larger decline in bond yields) fell by 1.0%. In APAC, only the TWD was stronger last week. The PHP fell 1.9% — mostly before the BSP decision was announced — and the JPY, THB and NZD were off by more than 1%. Other currencies were only slightly weaker against the dollar.

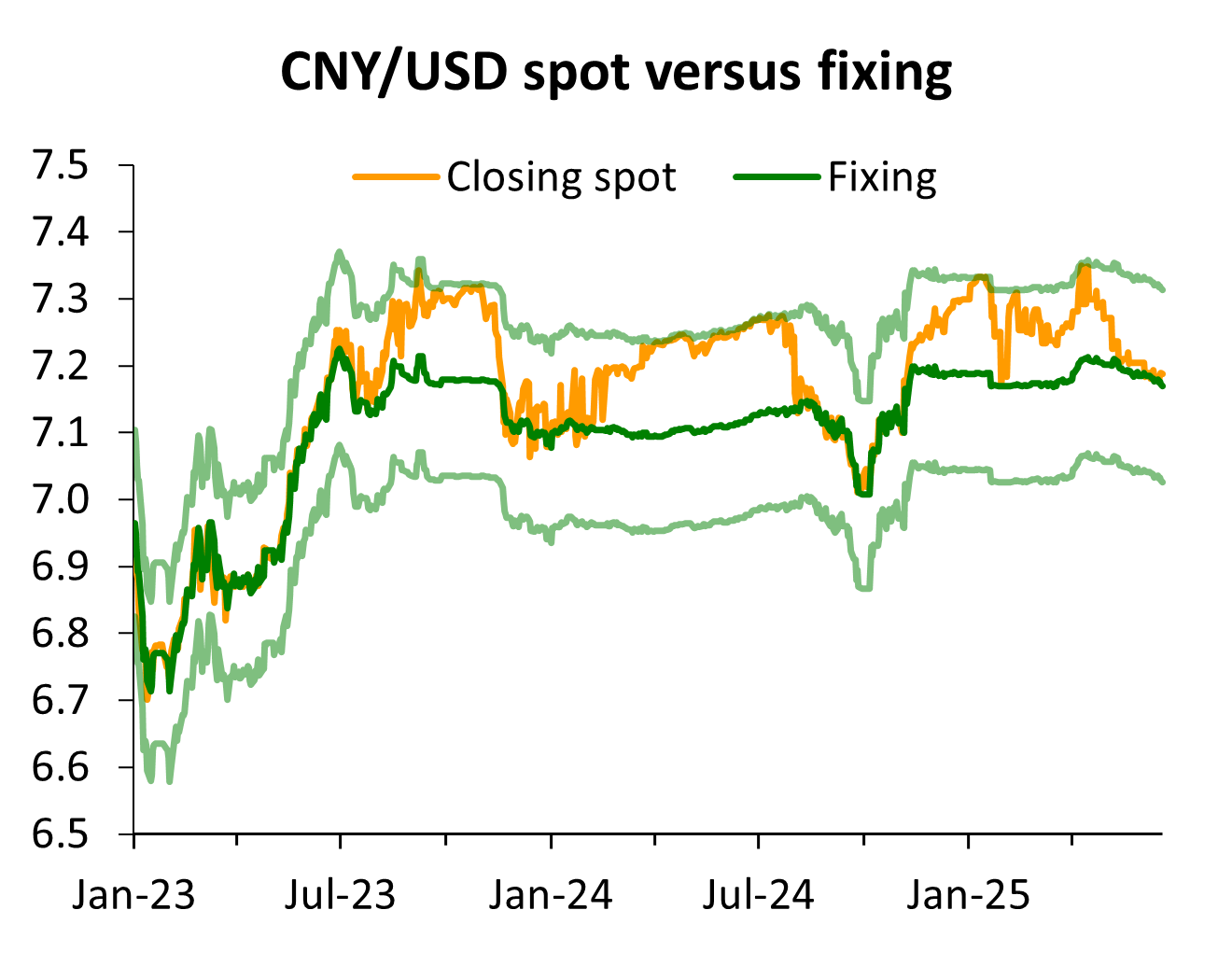

While the CNY was marginally weaker versus the USD last week, the trend since early April has been for it to appreciate gradually — cumulatively by 2.2% since April 10. Whereas in 2018 the PBoC responded to US tariffs by reversing the near-10% appreciation since early 2017, this time they allowed only a very modest and short-lived depreciation of about 1% before pushing the fixing stronger. Year-to-date, despite the tariff increases, the CNY has appreciated 1.5% against the USD.

I would argue, though, that this is mainly because other currencies have been even stronger. In terms that are perhaps more relevant to the PBoC, the CFETS trade-weighted CNY has depreciated by 5.5% since the end of last year. And during the last two weeks, the index has dropped slightly below what I hypothesized might be a kind of resistance level. So the PBoC has been able to achieve a trade-weighted depreciation — as it did in 2018 — without having to depreciate against the USD.

What to watch for this week

The Middle East conflict will no doubt dominate the news next week, but with only two weeks to go before his appointed deadline we should expect to hear at some point in the next week or so from Trump on his plans for tariffs after July 9. China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee meets this week, so there may be noteworthy messages about economic policy especially as deliberations on the next five-year plan enter a decisive phase. (The 15th FYP should be released this Fall.)

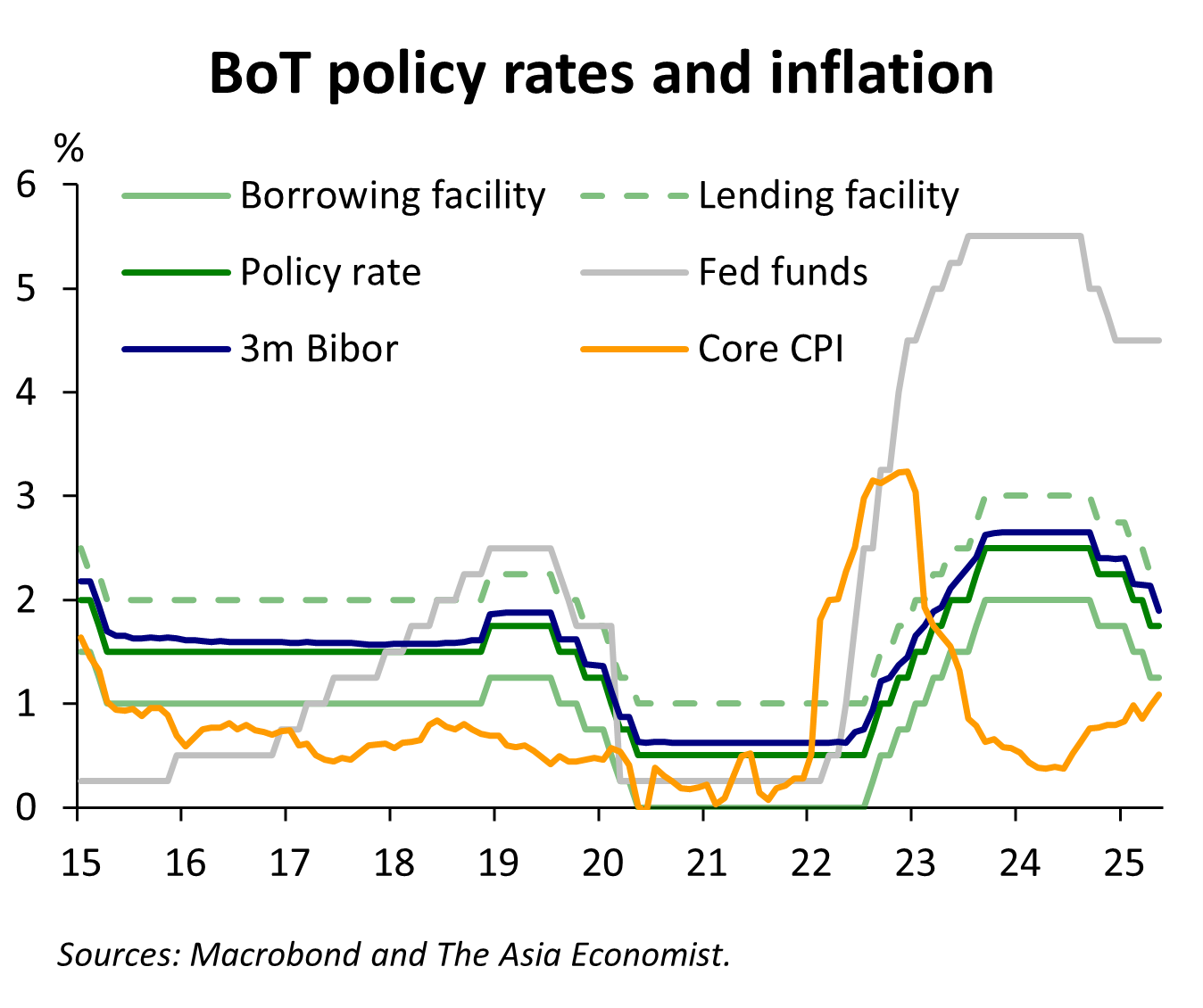

Only one central bank is scheduled to hold a policy meeting, the Bank of Thailand, and I think they would want to cut rates if the Middle East conflict — that is, oil prices — allows. Thailand is the most exposed to an oil price shock, and core inflation is already the highest in two years. It’s only barely inside the target range, though, so shouldn’t be constraint on cutting rates this week. But if oil prices are spiking higher, I’d expect the THB to be weakening and both would likely prevent the BoT from cutting rates.

Inflation rates for the month of May in Australia, Malaysia and the US (PCE) and in Tokyo for June will be reported this week although against the current geopolitical backdrop and tariff threats they may carry less weight than usual.

Share this post