As the July 8 deadline for agreeing new trade deals looms, President Trump said on Friday that he would decide on the new tariff rates and communicate them to all countries this week. The first dozen letters will go out on Monday but all countries will know their new tariff rate by Wednesday. I expect that the US’ largest trade partners — Treasury Secretary Bessent has been focusing on the 18 largest — will get individual notices, while most countries will simply be included in something like an “all others” list.

Because these tariff rates may differ from those announced on April 2, they will take effect on August 1, not July 9. So, we’ll possibly have another month where importers will rush to build inventories before tariffs go up.

While the current baseline tariff rate for all countries except China is 10% — China’s baseline tariff rate is about 55% — Trump gave a range of possible tariff rates to be announced this coming week, from 10% to 70%. So it’s quite likely that these announcements will have the effect of once again raising the average US tariff rate. Trump’s attitude towards tariffs is ‘the higher, the better’ and with inflation and the labour market steady and equities at a record high, there’s really nothing to stop him acting on this impulse.

And Bessent this morning took a slightly more hawkish perspective than I think the market has been expecting: countries that haven’t agreed to a new trade deal by Wednesday will see their tariff rate go up to whatever was announced on April 2. For most countries, that would represent a significant increase in the tariff. I think most investors expect most countries will see the current 10% rate rolled over.

Bessent and Hassett have said that countries still negotiating ‘in good faith’ might have the 10% rate continued, but the administration clearly isn’t negotiating with more than a handful of countries at any time. Indeed, both reiterated today the tired promise that the administration is close to finalizing deals with a great many countries over the next couple of days.

It is noteworthy though, that since Bessent essentially became the front-man from the US administration in the trade negotiations — that is, since April 9 — Trump has all but stopped talking up the many supposed virtues of high tariffs. Recall that tariffs were seen as providing a number of benefits:

Tariffs bring higher fiscal revenues — the White House cited a figure of USD1tn per year.

A tariff wall protects US industry and encourages foreign manufacturing to move to the US.

Tariffs were threatened as bargaining chips to convince other countries to lower taxes on US firms, whether this was digital services taxes, or value-added taxes on imports or just minimum corporate tax rates higher than the US rate.

Tariffs were threatened as bargaining chips to convince other countries to give up non-tariff barriers (e.g., health and safety regulations that differ from those in the US) or distorting practices like currency manipulation.

Tariffs were threatened to try to force countries to increase their defense spending.

These days, though, Trump mentions tariffs almost exclusively in the context of the revenues they bring in. But that’s running at about USD300bn annually at the current tariff level, well below his earlier promises.

While Canada’s digital services tax was cited by Trump as the reason to halt trade talks two weeks ago — talks that resumed when Carney’s government rescinded the tax — the UK’s DST wasn’t an obstacle to signing the Economic Prosperity Deal. The framework agreement (not yet a ‘trade deal’) with China makes no mention of currency manipulation or IP theft or any of a host of other grievances that motivated the Section 301 tariffs in 2018.

While most NATO countries have agreed to increase defense spending (broadly defined) to 5% of GDP the link between this goal and US tariff policy has been much less direct than I’d expected.

So, unless he returns to something like the April 2 tariff rates on the US’ largest trade partners, we’ll likely see this week that Trump has given up on using tariffs as an instrument for effecting a wholesale reordering of the global economy and rebuilding of US manufacturing. It does leave room for some trade partners to face higher tariffs. But if the tariff rate on China is 55%, is any other important trade partner going to face a higher tariff?

We’ll find out in a few days. I expect that, hot on the heals of getting his One Big Beautiful Bill passed, Trump will feel emboldened to levy whatever tariff he thinks appropriate. And that’s likely to be a lot higher than 10% for many important economies.

To help frame the discussion over the coming days, I repeat here the chart showing the baseline tariff rates applied to the main Asia Pacific economies that were announced on April 2. The ‘reciprocal’ tariffs announced on April 2 for Asia Pacific economies ranged from 10% to 49%, with a US imports-weighted average of 30%.

In addition to these ‘reciprocal’ tariffs, there are 25% tariffs on imports of automobiles and parts (except those from the UK and those from Canada and Mexico that are compliant with the USMCA — or CUSMA, if you’re Canadian — treaty) and 50% tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium and many products made of those metals (the UK faces only the original 25% tariff). Tariffs on semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and lumber have been proposed but not yet implemented.

A deal with Vietnam

On Wednesday, July 2, Trump announced on social media that an agreement had been reached with Vietnam to apply a 20% tariff on US imports from that country in exchange for Vietnam canceling all tariffs on imports from the US. The White House has described this as a one-sided deal, and it is. In Vietnam’s favour. Vietnamese people will now get tariff-free access to American goods where previously they paid a small tariff. US consumers will have to pay at least 20% to import from Vietnam.

The 20% US tariff, though, compares favourably with the 46% ‘reciprocal’ rate announced on April 2. The imports-weighted average Vietnamese tariff rate on goods from the US was formerly 7%. But the US formerly applied a 4% average tariff on imports from Vietnam. So this agreement has locked in at least a five-fold increase in the US tariff rate in exchange for a modest decline in the tariff applied by Vietnam.

“At least” because the other provision of the agreement, according to Trump’s post — and that post is all we know about this supposed deal — is that the US will apply a 40% tariff on ‘transshipments’ through Vietnam. Here it would be important to see detailed language because if the US defines ‘transshipments’ very broadly — goods with any significant Chinese content even if they are assembled in Vietnam — that 20% tariff rate might apply to small amount of Vietnam’s exports and the effective tariff rate could be a lot closer to the original ‘reciprocal’ rate.

Here’s a chart showing Vietnam’s imports from China and their exports to the US since 2014. Over the past twelve months, Vietnam imported USD158bn from China and exported USD132bn to the US. These two series are so closely correlated — a correlation coefficient of 0.97 — that it’s very tempting to argue that a substantial part of those imports from China are simply repackaged and sent to the US. That would be transshipment, pure and simple. No value added in Vietnam, just changing the packaging to make Chinese goods look like they were Vietnamese exports.

However, suppose Chinese firms were exporting electronic components to Vietnam that went into making dot matrix printers (for a time, and perhaps still, virtually all dot matrix printers in the world came from Vietnam) or Samsung phones (they made a big investment in Vietnam while Apple placed their bets on China). The Chinese components combined with components from other countries ended up in a product where the Vietnamese value added might be less than the total Chinese value added in the components. Would products like these be captured in the transshipments tariff?

Another observation from this chart. It is commonly asserted that transshipments through Vietnam really took off after Trump’s first trade war with China in 2018-19. But there was no obvious acceleration in Vietnam’s imports from China or its exports to the US in 2019. The post-Covid boom in US consumption shows up in higher imports to the US from most countries, including Vietnam, in 2021-22 but there’s no evidence here that there was a structural change in the pattern of imports from China versus exports to the US after 2018.

The point is, you can’t simply look at this chart and say that a substantial amount of Vietnam’s exports to the US are repackaged imports from China. I have no doubt that there is some genuine transshipment activity going on. But simply looking at levels of imports and exports isn’t going to tell us what proportion of Vietnam’s exports to the US are transshipped goods.

How important is Chinese tariff evasion?

The last couple of months of Vietnamese do look suspicious, so let’s explore this a little. Vietnam’s exports to the US have grown more quickly since April than they had in Q1 or the fourth quarter of last year. In Q4 last year, exports to the US rose 17%yoy; in Q1 this year they rose 22%. In April/May they rose 38%. Imports from China also grew more strongly, but only slightly. In Q4, imports from China rose 23%; in Q1 they rose 25% and in April/May they rose 28%. So a 3ppt increase in the rate of growth of imports from China but a 16ppt increase in the rate of growth of exports to the US.

It does look like Vietnamese exporters rushed to get goods into the US after the tariff pause, but it isn’t obvious that transshipment activity from China was an important contributor to that.

Even if we do attribute this increase in imports from China as an effort to circumvent US tariffs on direct imports from China, how much would Chinese exporters have benefited? Chinese exports to the US rose 11%yoy in Q4 last year but only 5% in Q1 — there was no pre-tariff export surge from China. But in April/May, exports to the US plunged by 28%yoy. As a counterfactual, had exports continued to grow at a 5% rate the total for April and May would have been about USD30bn higher.

If Vietnamese imports from China in April/May had grown at the Q1 rate of 25% instead of 38%, they would have been USD1.7bn lower. So maybe Vietnamese imports (or Chinese exports) were boosted by USD1.7bn because of increased transshipments. That’s 6% of the lost direct exports to the US from China.

But, you may say, Chinese exports to other countries went up unusually in April/May. Let’s look at Thailand. Imports from China look like they jumped up in April/May and indeed they rose 25%yoy versus 18% in Q1. Thai exports to the US rose 30%yoy in April/May versus 25% in Q1 (and 17% in Q4). Had Thai imports from China continued to grow at an 18% rate in April/May, they also would have been USD1.7bn lower. So again, if we attribute all of the increase in the growth of Thai imports from China in April/May to transshipment activity, China might have benefitted to the tune of USD1.7bn. Note that Thai exports to the US rose only slightly faster in April/May than they did in Q1. If the increase in imports from China reflected transshipment activity, there are still some goods waiting to be exported to the US.

Chinese exports to Cambodia and Laos also rose notably quicker in April/May as compared to Q1. We don’t have their export data for those months though so we can’t say whether exports to the US also increased more quickly. But even if we attribute all of the increase in imports from China in those two months to transshipments, that amounts to only USD0.7bn of trade.

Chinese exports to Mexico, another allegedly important transshipment node, actually grew more slowly in April/May than in Q1, which was slower than in Q4. Chinese exports to Canada did grow significantly more quickly in April/May than in Q1 but the US tariffs on imports from Canada already discriminated against non-USMCA (or CUSMA)-compliant goods. There would have been no expectation that a transshipment strategy would have worked.

So, even assuming all incremental exports above the Q1 rate of growth from China to Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos in April/May represented attempts to circumvent US tariffs, this would have offset less than 15% of the decline in direct exports to the US. Put another way, if the US shuts the door to pure transshipment trade, it may not carry much of a cost to the China or these countries.

But if the US views goods with any material Chinese content as illegitimate — not worthy of the 20% tariff rate applied to ‘purely Vietnamese’ goods, for example — this could be catastrophic. Asia Pacific supply chains would need to be completely remapped.

We won’t know how significant this risk is until we see a detailed writeup of the Vietnam deal agreed last week. But recall that the US-UK EPD excluded goods made by Chinese-owned firms in the UK — which would normally be viewed as UK content for tariff purposes — from the deal. I have flagged this risk frequently since Inauguration Day. An unstated objective of Trump’s tariff policy, I believe, is to exclude China from any supply chain — especially in electronic equipment, software and automobiles — that supplies US buyers.

So, while the focus for most people this week will be the headline figure on each country’s baseline tariff rate, I’ll be looking at whether other countries are also given a Vietnam-style dual-tariff structure and I’ll be looking for any evidence on how ‘transshipments’ are defined.

China’s CCFEA promotes a “unified national market”

The Chinese government is usually very good at telling us what they’re going to do; just not very good at telling us when. So it is the case that most policy changes can be found to have been anticipated by policy guidelines or priorities set out in public earlier. Often years earlier. Still, we do need to pay attention when the highest policy-directing body in the country — the Central Commission for Financial and Economic Affairs (CCFEA) — says anything.

The Commission met for the first time in over a year last week, which suggests that Xi Jinping felt he needed to light a fire under officials to better implement his policies — or to change direction. There were two main thrusts to the Commission’s concluding statement: building a unified national market and advancing the high-quality development of the marine economy. The former is probably of greater interest to economists, the latter probably of great interest to people abroad who care about the over-exploitation of global fisheries by ‘rogue’ Chinese fishing fleets.

The idea of a unified national market is not new, the Commission notes that it first took up the idea in 2022. In broad terms, this is about addressing local government protectionism and the resultant market fragmentation. The Commission identified the following tasks as central to this effort: standardizing market rules, infrastructure, government conduct, market regulation and law enforcement, and resource allocation. For example, local government procurement should not give preference to local firms. Infrastructure and market rules and regulations should be standardized across the country.

But it was the following phrase that is the most interesting. Quoting from People’s Daily: “Policymakers called for steps to regulate disorderly low-price competition in accordance with laws and regulations, guide enterprises to improve product quality, and promote the orderly exit of outdated production capacity.” I noted a few weeks ago that policymakers were trying to end the EV price wars and that may be uppermost in the Commissioners’ minds last week. But the concept is broader than that and linked to the “orderly exit of outdated production capacity”. Excess capacity breeds disinflationary pressure as unprofitable firms seek to stay afloat by dumping product on the market at ever-lower prices.

Providing a mechanism for the “orderly exit” of unprofitable firms has been devilishly difficult to achieve in a mixed economy where many of the weakest ‘zombie’ firms are state-owned. There are bankruptcy procedures in place in China, but we’ve seen how difficult it has been to put this into effect even for privately owned property developers in recent years.

So don’t hold your breath that anything’s going to change suddenly, but this is essentially Xi Jinping telling local officials that they need to stop protecting their patch against other (domestic) firms and start looking for ways to let unprofitable local firms be closed down. This cannot be ignored.

Creating a unified domestic market takes on added urgency when one of your biggest export markets essentially closes itself off from you by imposing insurmountable tariffs. Not coincidentally, creating a unified domestic market is also a top priority of the Carney government in Canada.

China (and Canada) hasn’t given up on the US or external demand in general, but the tariff threat and the unwillingness of the EU to have China’s US exports diverted there creates a need for “improving channels for converting exports into domestic sales”. Easier said than done when a substantial part of your exports are intermediate goods made to fit into very specific supply chains abroad. There may not be any domestic demand for these products. But it’s the right attitude.

On the development of the marine economy, “the country will expand and upgrade marine industries, promote the orderly and regulated development of offshore wind power, modernize deep-sea fishing, and develop marine biopharmaceuticals and biological products.” China will also “deepen its participation in global ocean governance”. No mention of overfishing or the need for enhanced environmental protections, sadly.

A mixed week for equities and bonds; the dollar continues to weaken

US markets looked favourably on the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill, with equities rising 0.8% on the day the House passed the bill and 1.9% on the week as a whole. US Treasury yields rose 6bps last week, hardly indicative of the kind of market discipline of reckless US fiscal policy that some commentators would have us believe. More noteworthy, still, is the decline in the value of the US dollar, which has now depreciated more than 10%ytd against other major currencies — about 7.5% in broad trade-weighted terms.

US stocks outperformed all APAC markets except Thailand — which responded positively to the suspension of Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra by the Constitutional Court. South Korean stocks had only their second decline in twelve weeks but had actually been up more than 2% through Thursday. Chinese stocks were down more than 1% on the week — there were no major announcements out of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee meetings — and Philippine stocks were down 1.2%. Asia ex-Japan was down about 0.3% on the week. Stocks in Japan were down 0.4%. Stocks in Malaysia, Vietnam, and New Zealand were up more than 1%.

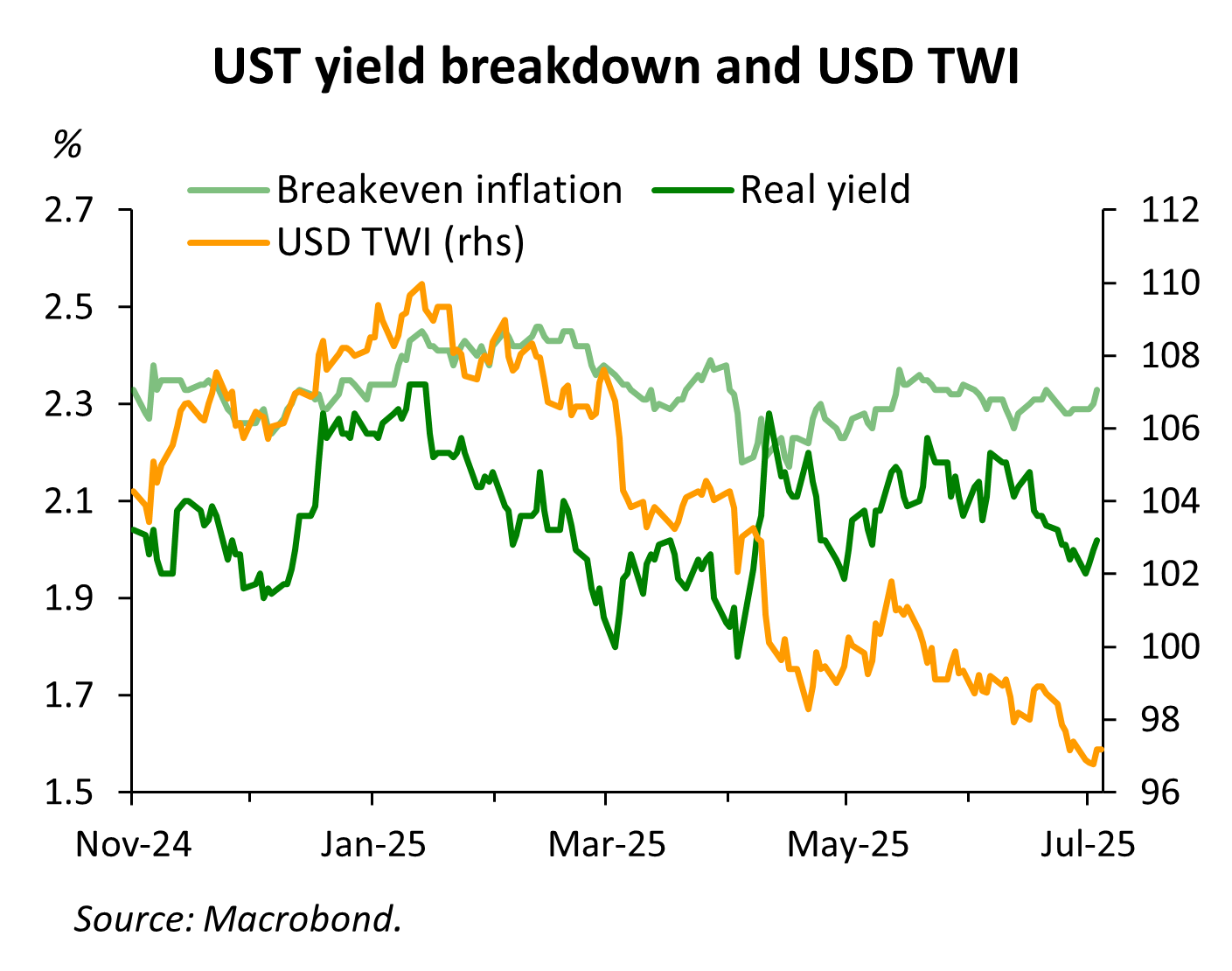

US 10yr Treasury bonds sold off by 5bps on Thursday, ending the week at 4.35%. The inflation indexed yield of 2.02% is essentially what it was on the eve of Trump’s election, while the breakeven rate of inflation of 2.33% is only 5bps higher than it was then — and lower than it was during all of Q1. This is not a bond market that is penalizing US lawmakers for unnecessarily expansionary fiscal policy.

Where fixed income markets did respond to the OBBB passage was in expectations for the Fed. Any talk of a July rate cut disappeared and indeed the market is now pricing in only two rate cuts by year-end. This despite renewed pressure from Trump on Powell to cut rates faster. The dollar appreciated a little on Thursday after the OBBB passage but still ended the week down 0.2% against the other major currencies.

Elsewhere, yields were mixed — rising about in line with US yields in New Zealand, Australia and Hong Kong and falling more than 6bps in Singapore, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Bond yields in China and Japan have been pretty stable recently but have fallen since late May.

Among the higher-yielding markets, bond yields in Indonesia have been trending down since mid-April, while yields in India have been trending up since early June. Philippine yields fell last week but from the highest levels in nearly a year.

While the dollar rose on Thursday against other advanced economy currencies, over the course of the whole week it was lower. And most APAC currencies likewise appreciated against the dollar. The Thai baht led the way here too on hopes (I think misplaced) that the political stalemate has been resolved with the Prime Minister’s suspension. But currency moves, like bond market moves, were pretty modest overall.

The CNY appreciated 0.1% against the USD last week — the spot rate (and fixing) is now at its strongest level of the year. As many observers have noted, this is in stark contrast to the 8% depreciation versus the USD over just four months after the 2018 tariffs were imposed. But I think it’s important to recognize that against other currencies, the CNY has depreciated this year. Taking the BIS country weights, I construct a CNY NEER excluding the USD. That index has depreciated more than 7% since the beginning of the year.

Facing a tariff of at least 55% on sales to the US, I think the Chinese authorities have all but written off exports to the US. There is no acceptable rate of depreciation versus the USD that would have a meaningful impact in dampening the effect of the tariffs — even assuming the goods are priced in CNY not USD. If that’s how they’re thinking, then allowing the currency to appreciate against the USD — as almost all currencies have — but to depreciate significantly against other trade partners is a smart strategy. The US can’t argue that China is devaluing to try to maintain competitiveness in the US while China does gain competitiveness in other markets through a weaker currency. Note that in REER terms, the CNY has already depreciated more than 5% this year.

Benign inflation reports in Indonesia, the Philippines and South Korea

June inflation reports support the dovish stance of policymakers in Indonesia, the Philippines and South Korea. Core inflation fell in Indonesia for a second consecutive month, and was stable at low rates in the other two countries.

Rising food prices pulled headline inflation up a notch in Indonesia, but the rate remains near the lower end of the target range. Core inflation eased for a second consecutive month, falling to 2.37% from 2.50% in April. I highlighted what I thought was a dovish tone to the Bank Indonesia statement in June and this inflation report will make it easier to cut rates later this month.

The Bank of Korea’s monetary policy board meets this Thursday, and the June inflation report likely won’t impact their decision either way. Headline inflation rose to 2.2% from 1.9% in May but core inflation was unchanged at 2.0%, which is the central bank’s target. But the Board had struck a very dovish tone when they cut rates in May and I expect they’ll cut rates again this week. Trump’s tariff announcements are more likely to lead to a weakening of the economic outlook than an improvement. South Korea’s ‘reciprocal’ rate on April 2 was 24%, so the risks are perhaps tilted towards being hit with an increase in their US tariff this week.

The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas doesn’t have a scheduled policy meeting this month but the June inflation report might make it easier to respond to US tariffs with an emergency rate cut. Headline inflation has been below the bottom of the target range for four months, edging up a tenth to 1.4% last month. Core inflation has fallen to 2.2%, the lowest rate in three years. Measured against core inflation, the real policy rate is still very high at 3.6%.

What to watch this week

Trade-related news will likely dominate this week. Expect Trump to tweet out countries’ new baseline tariffs as soon as he delivers the letters. The theatre is as important as the substance to him and he’ll want to take personal credit for these tariffs. Keep the first chart in this post with you so you can compare the new tariff rate to the April 2 rate. Again, my bias is that the new rate will be lower than the April 2 rate but higher than the current 10% rate for most economies that matter for US trade.

Four APAC central banks have policy meetings this week. The Reserve Bank of Australia Board meets on Tuesday. Cash rate futures continue to price in a rate cut, but with credit growth rising and the labour market still strong, I think the Reserve Bank might deliver a hawkish cut to dampen expectations of another cut as soon as August. Since Australia’s April 2 tariff rate was 10% and they run a trade deficit with the US, tariff news is unlikely to be a direct threat to the Australian economy. But possibly news about other countries’ tariffs will require an adjustment to the economic outlook.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand Board meets on Wednesday and there too the tariff news between now and then is unlikely to pose a direct threat to the economic outlook necessitating a change in policy. At the last policy meeting in May, the Board signaled that they thought they were nearing the end of rate cuts. Their forecast has another 40bps of cuts by Q1 next year — they have already cut by 225bps — but I think their preference would be to wait until after the Q2 CPI report, which comes later this month.

Bank Negara Malaysia’s monetary policy committee also meets on Wednesday and I expect they will continue to keep rates steady. While headline inflation has slowed recently, the core rate of inflation has been essentially stable for over a year. There is more potential tariff risk here than in Australia or New Zealand — Malaysia’s April 2 ‘reciprocal’ tariff rate was 24% versus those countries’ 10%, but the central bank’s current assessment is that the economic outlook remains positive, buoyed by rising wage growth and strong domestic demand. The data since then have been mixed — wage growth rose to a 10-month high but manufacturing output growth slowed. A high US tariff might be enough to tip the balance in favour of cutting rates, but if that information is not yet available I expect they’ll keep rates unchanged.

Finally, the Bank of Korea’s Monetary Policy Board meets on Thursday. As I explained above, I expect they’ll cut rates again this week.

Share this post